Providence Walks: Early Black History Tour

This walking tour is self-guided.

Click here to view a virtual version of the walking tour.

Printed maps are available at our Visitor Information Center at the Rhode Island Convention Center. Click here to view a full-size PDF of the map.

From the Beginning: 1636–1865

Providence history is Black history, from the early days of the colony to today. Roger Williams founded Providence in 1636 on land inhabited by the Narragansett, Wampanoag and other tribes. In 1737, British colonizers turned to the business of the trans-Atlantic slave trade and slavery to support themselves. They imported captive Africans who helped to build this colony and others throughout the Western Hemisphere.

Providence elites developed a system of laws and codes to uphold the business and the structure, and to ensure profit for the owning class. By the mid-1700s, Rhode Island slave traders were a dominant force in the trans-Atlantic slave trade, and the majority of the town’s and colony’s economy was connected in some way to the trade, including the production of goods such as rum, candles and iron. There was a clear economic interdependence with plantations in the Caribbean, Southern colonies and even Suriname, where ships docked to trade captives for goods like sugar and cotton. In 1764, Governor Stephen Hopkins wrote, “Without this [slave] trade, it would have been and will always be utterly impossible for the inhabitants of this colony to subsist themselves, or to pay for any considerable quantity of British goods.” The upper-class colonists would also have had to cook and clean for themselves.

The majority of the early Providence population participated in and/or benefited from the slave trade. But over time, questions were raised. Enslaved people resisted in many ways, and began to speak out publicly. Some were manumitted (released from slavery) by their owner, others by circumstance. Free Black people and abolitionists called for change. The Revolutionary War prompted a wave of Black freedom, followed by the Gradual Emancipation Act in 1784, and freed people started to build free communities, advocating for, and even purchasing, the freedom of beloved family and friends.

As this was unfolding, many white people still clung to the system that built this wealth and created a powerful ruling class. Abolition was not an event; it was a process. Slowly, the role of slavery within the state’s borders decreased, but this did not end Rhode Island’s economic and social entanglement with the system. For example, Rhode Island was one of the largest producers of “Negro cloth” from cotton imported from the South, supplying the plantation market with cheap, low-quality fabric worn by enslaved people.

The legacy of slavery and its aftermath is deep, uncomfortable, and, in many ways, has been hidden and silenced. Despite this, generations of Black Rhode Islanders lived and thrived. Taking this tour is an act of remembrance, which honors the lives of those whose stories are only partially known, but who contributed significantly to the city you see today.

This tour was written and researched by Elon Cook Lee and Traci Picard, with Julia Renaud, all from The Center for Reconciliation.

Providence Personalities: Early Black History

Thomas Howland

Thomas Howland was the first Black man elected to public office in Providence in 1857. He worked as a grocer and stevedore but was denied a United States passport immediately after the Dred Scott decision. He left Providence for Liberia due to this discrimination.

Cudge Brown

Cudge Brown was enslaved by Moses Brown and then manumitted by Brown in 1768. He married freedwoman Phillis, and they later raised a family on Olney Street. He grew a garden that was passed down for generations and worked as a teamster, carting materials all over Providence and beyond.

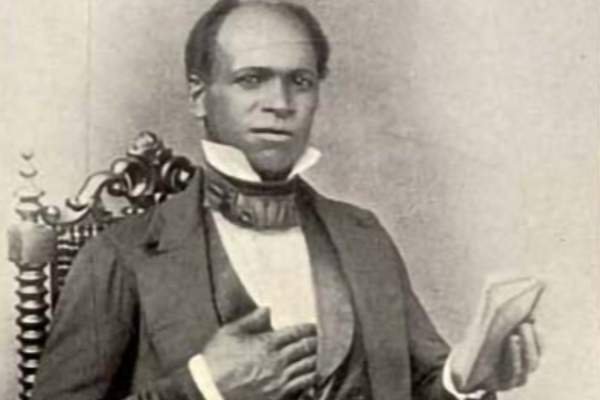

William J. Brown

William J. Brown was born free in 1814, grandson of Cudge and part of the extended Brown family of enslaved and freed people. He was a keen observer who knew the Black community well. He worked as a shoemaker and minister, and in 1883 wrote a book, “The Life of William J. Brown,” about his experiences.

St. Jago Hopkins

St. Jago Hopkins grew up enslaved in the Stephen Hopkins household. He was manumitted in 1772 and worked as a rigger. He married Rose King in 1778 and later a woman named Abigail, with whom he bought a house in 1789. He had five surviving children: Samuel, Amos, Rosannah, Elizabeth and Sally.

Elleanor Eldridge

Elleanor Eldridge was a free Black and Narragansett woman born in 1794 with an entrepreneurial spirit. She owned a home on Spring Street, which was taken from her, but she sued to get it back. To help fund her legal fight to regain the lost property, she worked with author Frances McDougall in 1843 to pen “Memoirs of Elleanor Eldridge,” recounting her life. She died in 1862.

Emmanuel “Manna” Bernoon

Emmanuel “Manna” Bernoon and his mother, Amey, were enslaved by the Gabriel Bernon family. After manumission in 1736, Manna founded and ran the first Oyster and Ale House in Providence on Towne Street (now South Main Street) near the working waterfront. He lived with his wife Mary, a washerwoman, in their own home on Stampers Street. At the time of his death, he had an eclectic inventory of clothing and objects. He died in 1769 and was buried in North Burial Ground.

George Henry

George Henry was born into slavery in 1819 in Virginia but escaped to Providence. A strategic thinker and skilled mariner, he was an entrepreneur, a community leader and sexton at St. Stephen’s Church; worked for school integration; and wrote a memoir, “Life of George Henry.”

Shoemaker Family

When Jacob Shoemaker died without a will and no heirs in 1774, the six people he had enslaved became the property of Providence. Listed as “Shoemaker’s Negroes” in the census, the reality is that despite the law, Thomas, Phebe and their four children were not property but people. They were freed by Providence on the condition that their labor was not needed to pay their enslaver’s debts. (It wasn’t.) Thomas helped to build Market House.

Fibba Brown

Fibba Brown was an enslaved servant of Stephen Hopkins. She lived and worked in his house for many years. Waking early, she prepared meals, kept the fires burning, cleaned the house and cared for the Hopkins family, as well as her own children. She was finally freed and joined the Olney Street household of her husband Bonner Brown. She died in her 90s in 1820.

Pero Paget

Pero Paget was a laborer and stonemason enslaved by Henry Paget. He contributed skilled labor to buildings throughout Providence, including Market House and Brown’s University Hall, as well as bridges and roads. He died in 1780 at age 72 and was buried in North Burial Ground.